Archive 1945

“The year 1945 is opening gloomily for the Allies. Fighting still goes on in Athens. The Lublin Committee has added another twist to the tangled knot of Polish politics by declaring itself the provisional government of Poland. Across the Atlantic, American criticism of Britain and distrust of Russia show but little sign of abating. Militarily, too, the outlook is disappointing. The Rundstedt offensive has been checked, but that it should have succeeded at all grievously contradicts the high hopes of last summer.”

“No motor-cars, refrigerators, pianos, vacuum cleaners, tennis or golf balls have been produced since 1942, and only very few radios, bicycles, watches and fountain pens.”

“His talk was full of the German myth, the rebuilding of bigger and better German towns, the failure of the bourgeois world and the new dawn of National Socialist principles…He appears to have passed beyond even a remote interference in the strategy of the war and to be now little beyond the focus for the despairing nationalism of the German people.”

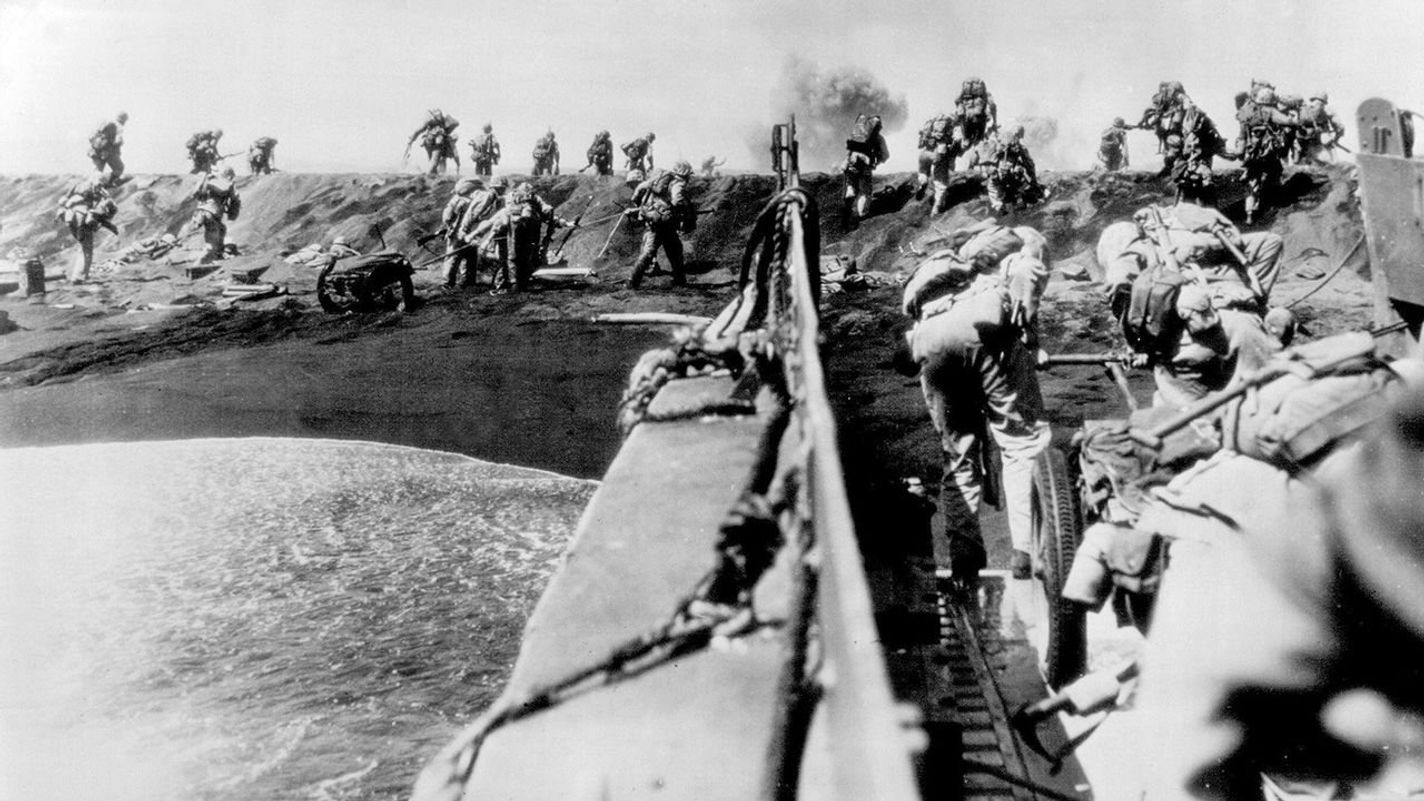

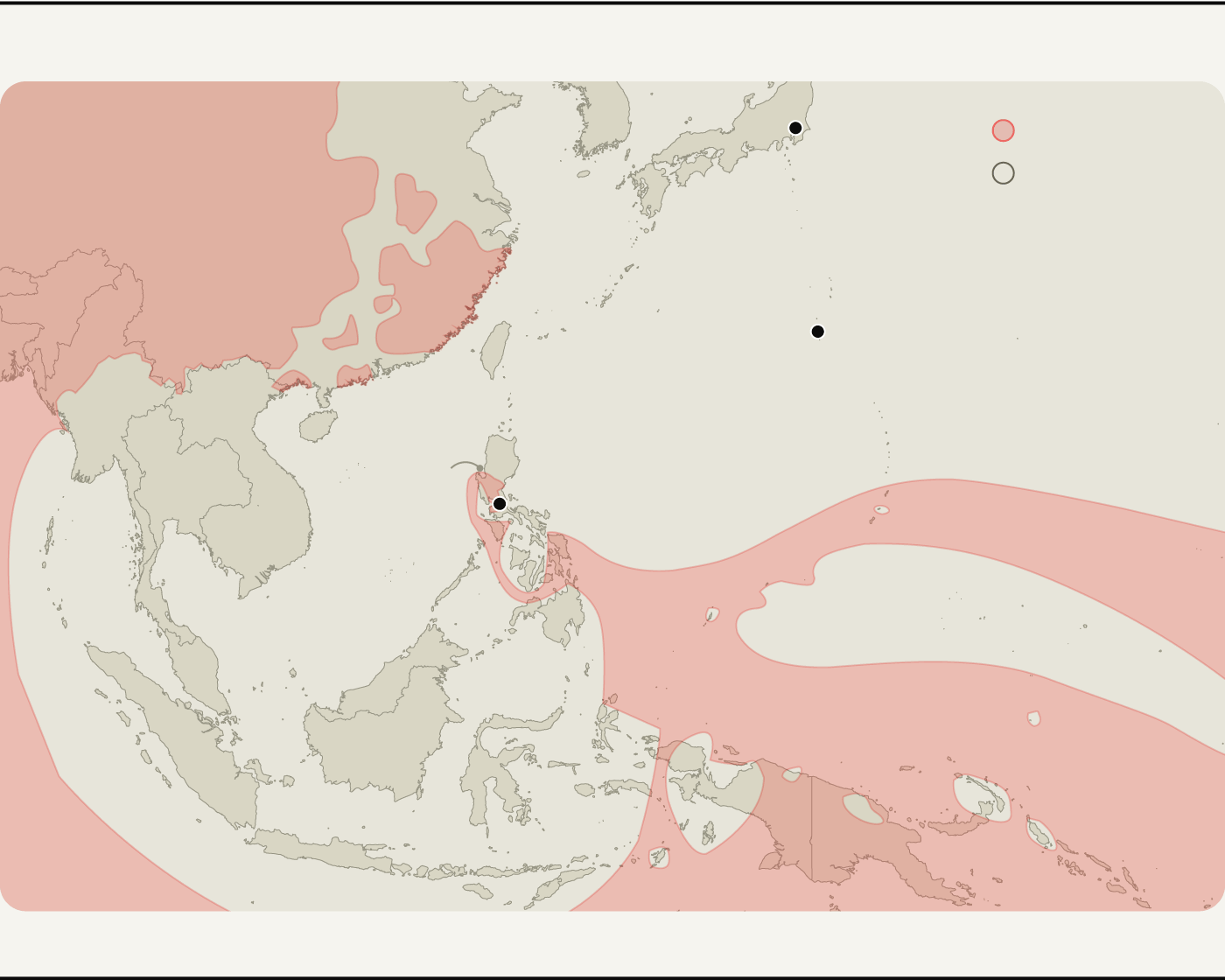

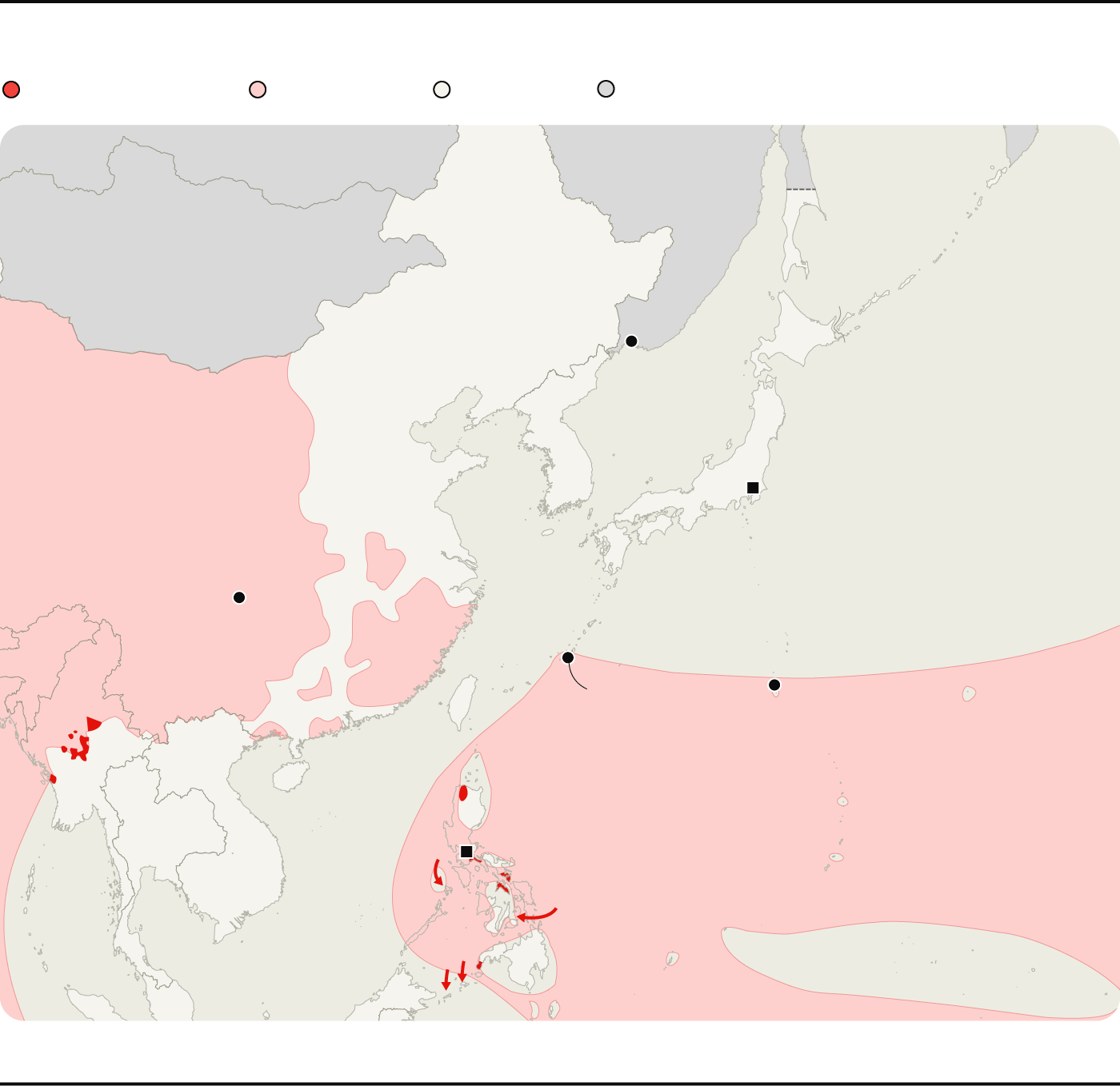

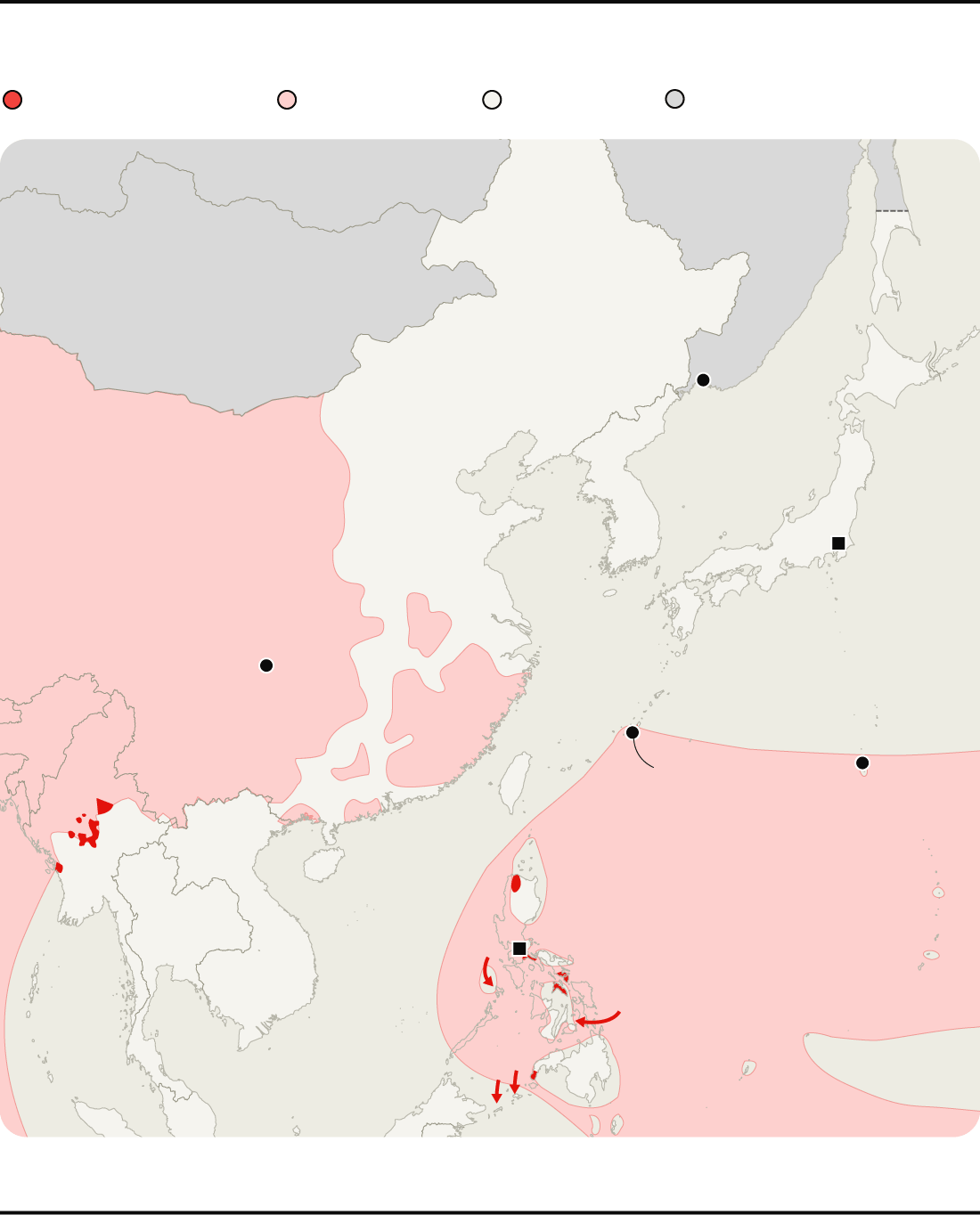

“The landing on Luzon, the largest of the Philippine Islands, has begun. Great American forces have already established four bridgeheads, and although tough fighting lies ahead, there can be no doubt that the last phase in the recapture of the Philippines has begun and that the end is in sight.”

“In face of this situation—a potential Greece of the Far East, on a vaster and even more damaging scale—what policy ought the allies to pursue? China’s allies suffer from this grave disadvantage, that foreign intervention is always unpopular, and interference, if pressed too far, may end in nothing but violent dislike for those who have done the interfering…It is therefore with the utmost patience and tact that the Allies must press on both sides in China the need for unity.”

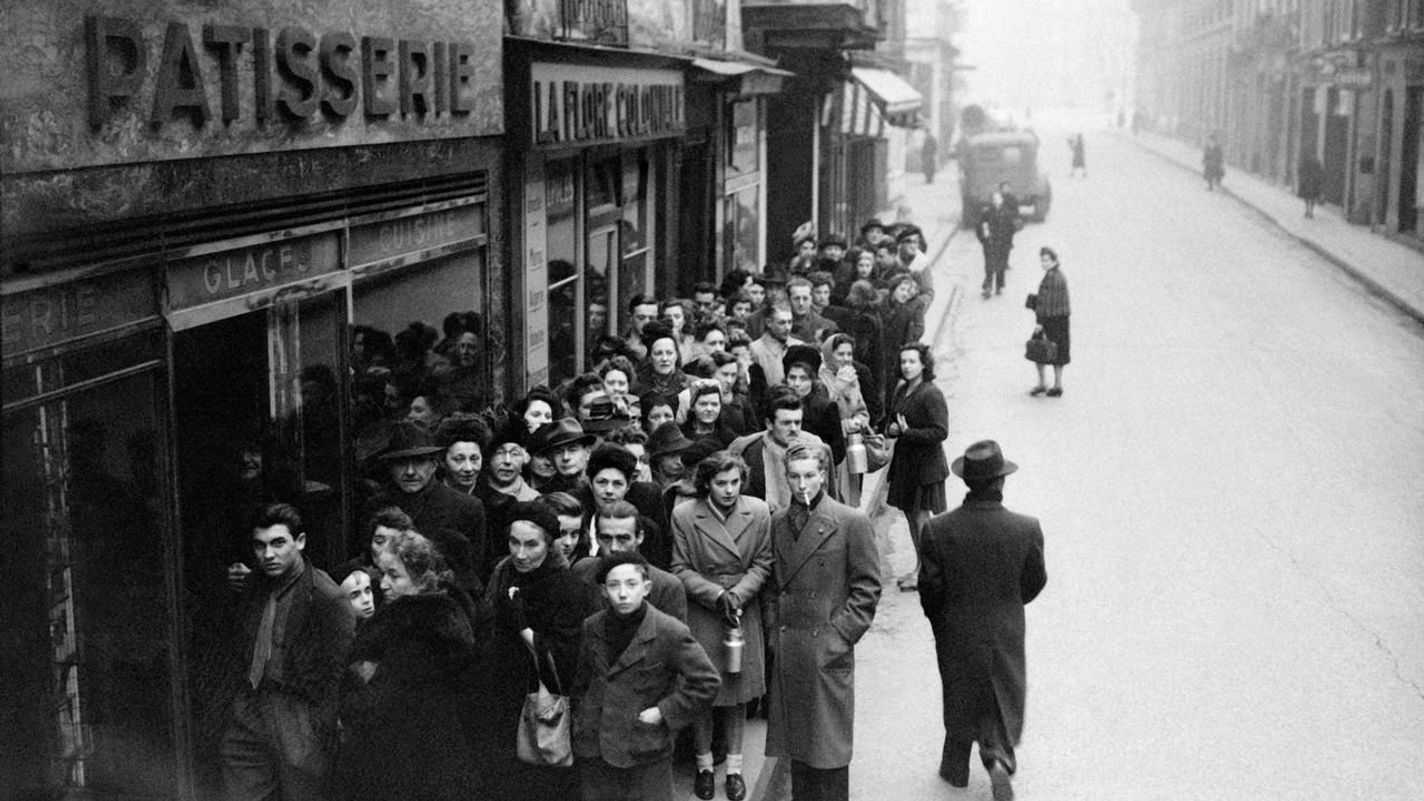

“France has been allowed to drift into a position from which it must be speedily rescued. The population of Paris and of many other towns is shivering from lack of coal; during the first week of this month daily deliveries to Paris averaged little more than 10,000 metric tons, a mere fraction of normal requirements and barely enough to meet the urgent need of hospitals, schools and essential public services.”

“A complete veil of secrecy has fallen over Russian-occupied Europe. Odd hints and pieces of information point to some political tension here and there, and to some extent armed clashes between Russians and local forces. But secrecy has made it almost impossible to gauge the scope and importance of these disturbances. Whatever its policy in the occupied territories, the Russian Government is not handicapped by the exacting demands of democratic opinion and parliamentary control.”

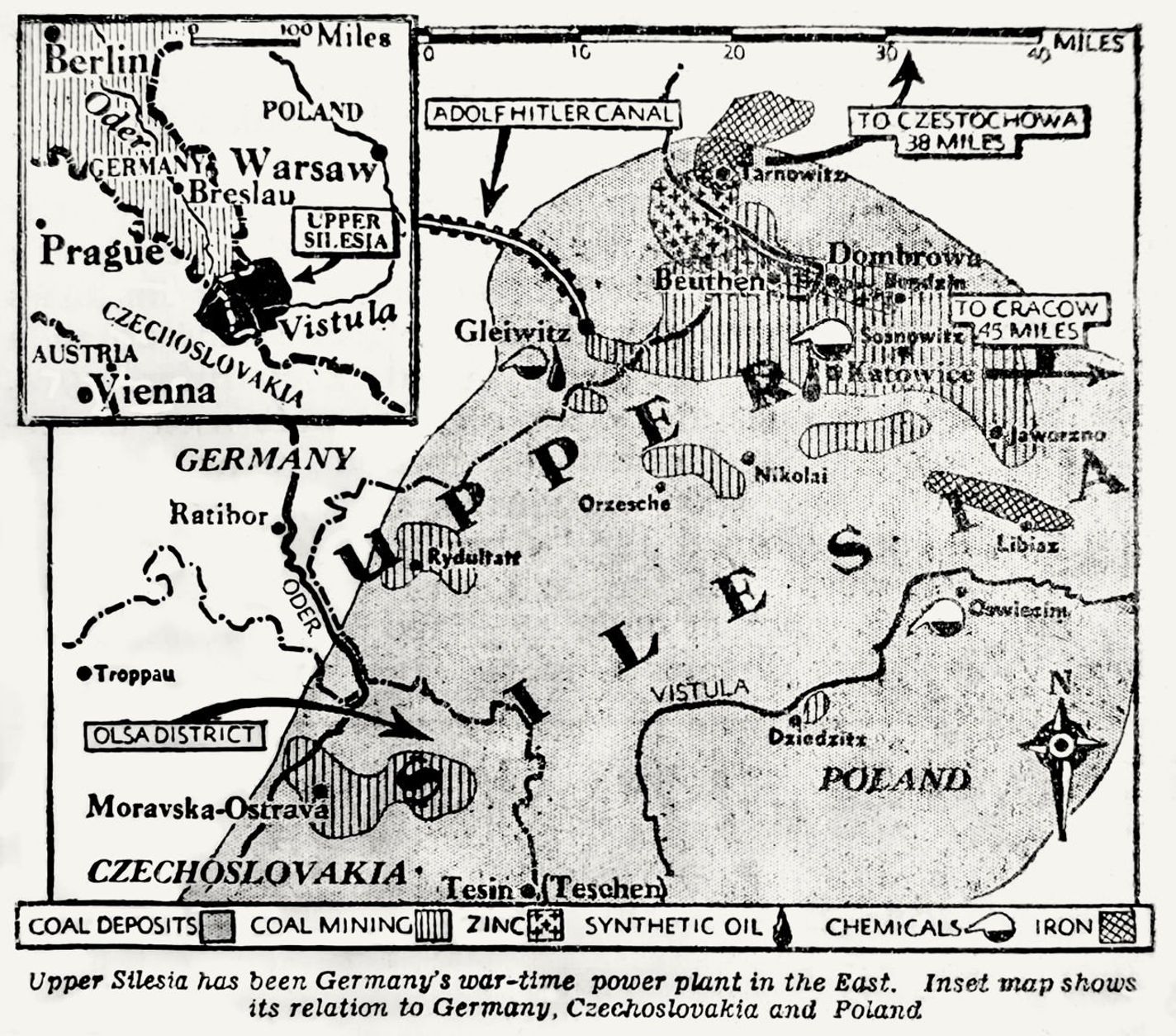

“It cannot be doubted, therefore, that during the last two years Upper Silesia has developed numerous new industries. Apart from new chemical plants, large factories for all kinds of war material have sprung up all over the area, usually being situated away from inhabited places and well camouflaged by forests and hills.”

“The destruction of German militarism and of the German General Staff appears for the first time beside the annihilation of Nazism. The punishment of war criminals is reaffirmed. For the first time it is officially suggested that the Germans can eventually win ‘a decent life…and a place in the comity of nations.’ The ambiguities concern the economic and territorial settlement.”

“Everything turns on the interpretation given in practice to such terms as ‘democratic,’ ‘free and unfettered elections,’ ‘democratic and non-Nazi parties,’ ‘not compromised by collaboration with the enemy.’ If these words mean what they say, and what British and Americans understand them to mean, then clearly a great advance has been made. To this only the execution of these plans can give a final answer…There is, however, one sure test. If the governments established under the Crimea Declaration and the communities they administer show healthy signs of dispute, differences of opinion, and genuine independence of political approach, it will be safe to say ‘Amen’ to the present proposals.”

“First of all, the Russian armies are decidedly superior in numbers. Once the break-through was achieved, the speed of the advance was accelerated by the dense network of roads. The rivers, lakes and swamps, common to eastern Germany and western Poland, were therefore no obstacle. Under these conditions, a mere stabilisation of the fighting on a new front along the Oder line cannot be more than a temporary halt, if it can be achieved at all.”

“Behind this propaganda, which has never before used so many superlatives in describing the plight of refugees and the danger to the Reich, the reorganisation of the armies is undoubtedly progressing. Political opposition from generals and other officers, which provided the danger-point last summer, seems to be absent; in fact, after the purge of last year, effective opposition hardly seems likely at the moment. So far, the Allies’ policy of unconditional surrender appears to have resulted in an ‘Unconditional Defence.’”

“These are black weeks for the leaders and people of Japan. The Philippines are all but lost. American forces are landing on Iwojima, only six hundred miles from the coasts of Japan. Tokyo and other towns have received the first of what promises to be a continuous series of bombing raids from over a thousand American aircraft. At the same time, the news from Europe—the Crimea Conference and the sweeping Russian advances into Germany—suggests that the Allies may soon be free to concentrate all their resources against Japan.”

Asia Pacific, Feb 15th 1945

Allied control

Tokyo

Enemy control

JAPAN

CHINA

PACIFIC

OCEAN

Iwo Jima

Burma

PHILIPPINES

SIAM

Lingayen

Gulf

Manila

french

indochina

Dutch east indies

Source: United States government

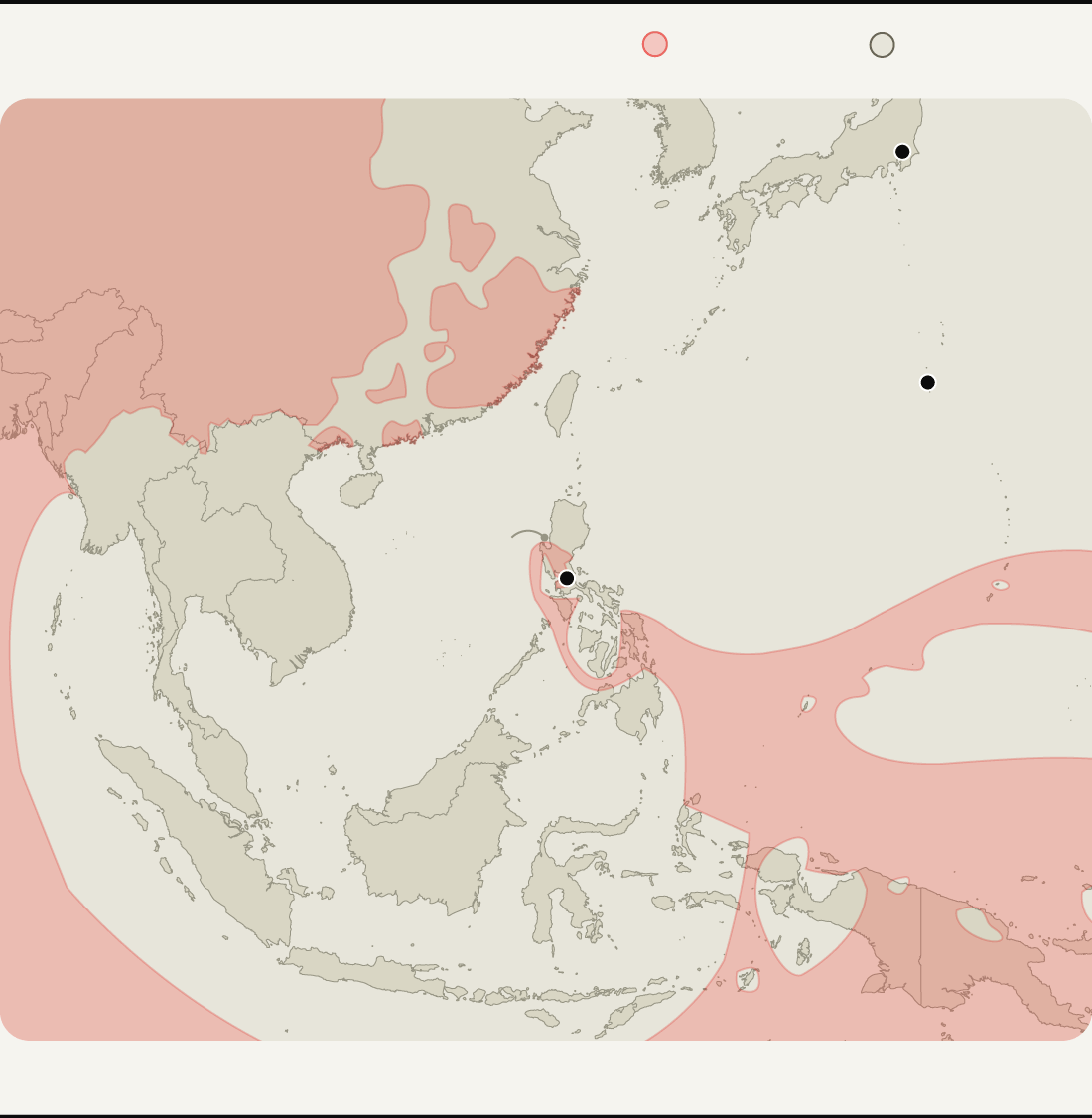

Asia Pacific, Feb 15th 1945

Allied control

Enemy control

Tokyo

JAPAN

CHINA

Iwo Jima

Burma

PACIFIC

OCEAN

PHILIPPINES

SIAM

Lingayen

Gulf

Manila

french

indochina

Dutch east indies

Source: United States government

Asia Pacific, Feb 15th 1945

Allied control

Enemy control

JAPAN

Tokyo

CHINA

Iwo Jima

PACIFIC

OCEAN

PHILIPPINES

Lingayen

Gulf

Manila

Source: United States government

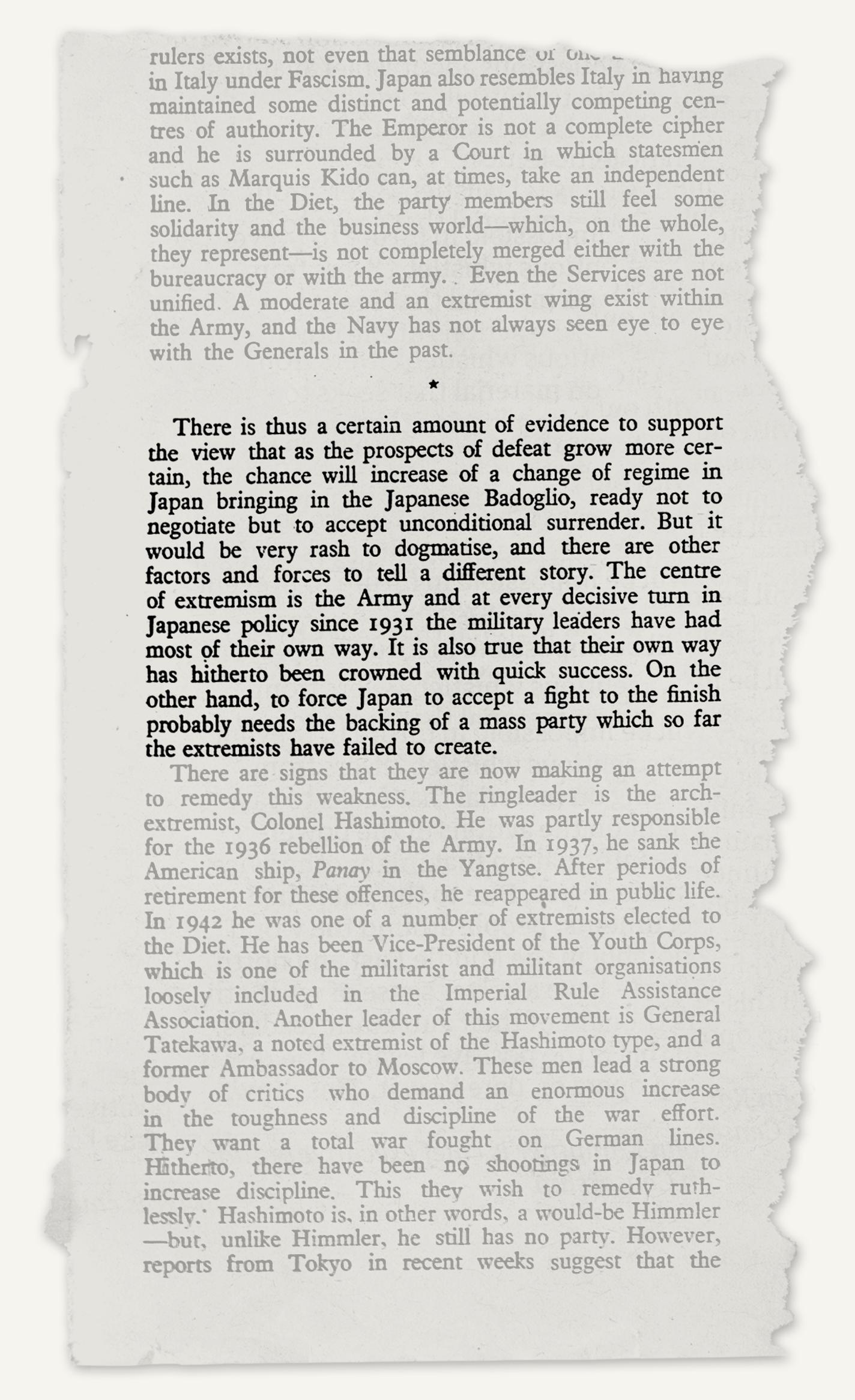

“There is thus a certain amount of evidence to support the view that as the prospects of defeat grow more certain, the chance will increase of a change of regime in Japan bringing in the Japanese Badoglio, ready not to negotiate but to accept unconditional surrender. But it would be very rash to dogmatise, and there are other factors and forces that tell a different story. The centre of extremism in Japan is the Army and at every decisive turn in Japanese policy since 1931 the military leaders have had most of their own way. It is also true that their own way has hitherto been crowned with quick success.”

“No one now believes that the ‘last all clear’ will herald an immediate resumption of pre-war life with its abundance of good things. The continuance of rationing, with only gradual relaxation, is accepted as inevitable. Nonetheless, the armistice with Germany will release a flow of spending—however much discouraged officially—which will pour through every gap not closed by definite per caput rationing. The end of the war will break the mould in which the social conscience has been set for the last five years. Few will give a second thought to saving fuel or money, making do and mending, or taking journeys which on any definition are not ‘really necessary.’”

“The catering industries’ need for Government assistance is a matter of urgency. The lifting last year of the defence area ban on travellers resulted in an influx of visitors to East and South-East coast resorts which they were ill-prepared to receive and with which the railways could not cope. This year the number of holiday-makers is likely to be considerably larger, in view of the mood engendered by the military situation. People are now prepared to permit themselves some relaxation of effort. If the Armistice should come before the main holiday season, the demand for holidays will be heightened. The immediate prospect is one of an acute shortage of holiday accommodation.”

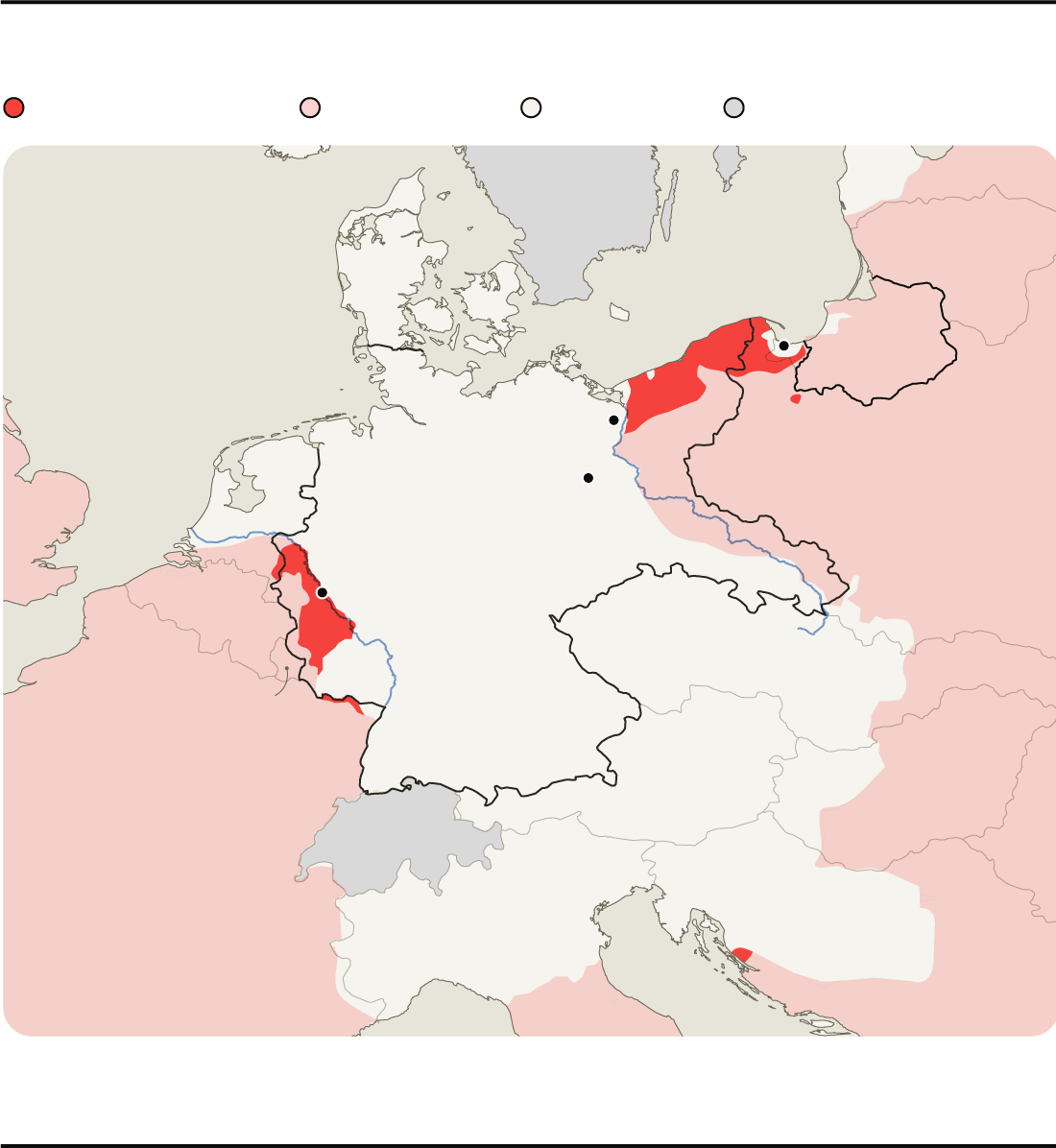

“The first week of March saw battles on the Rhine and the Oder which opened the final chapter of the European war. The Allied armies in the west are reaching the Rhine on a long front, from Coblenz to the Dutch frontier. Rundstedt, hopelessly outfought, has not even been able to keep the big towns on the left bank of the Rhine as bridgeheads for the Wehrmacht...His real objective can only be to delay the establishment of Allied bridgeheads across the Rhine for as long as possible. Even some success in this would bring no real relief to Germany.”

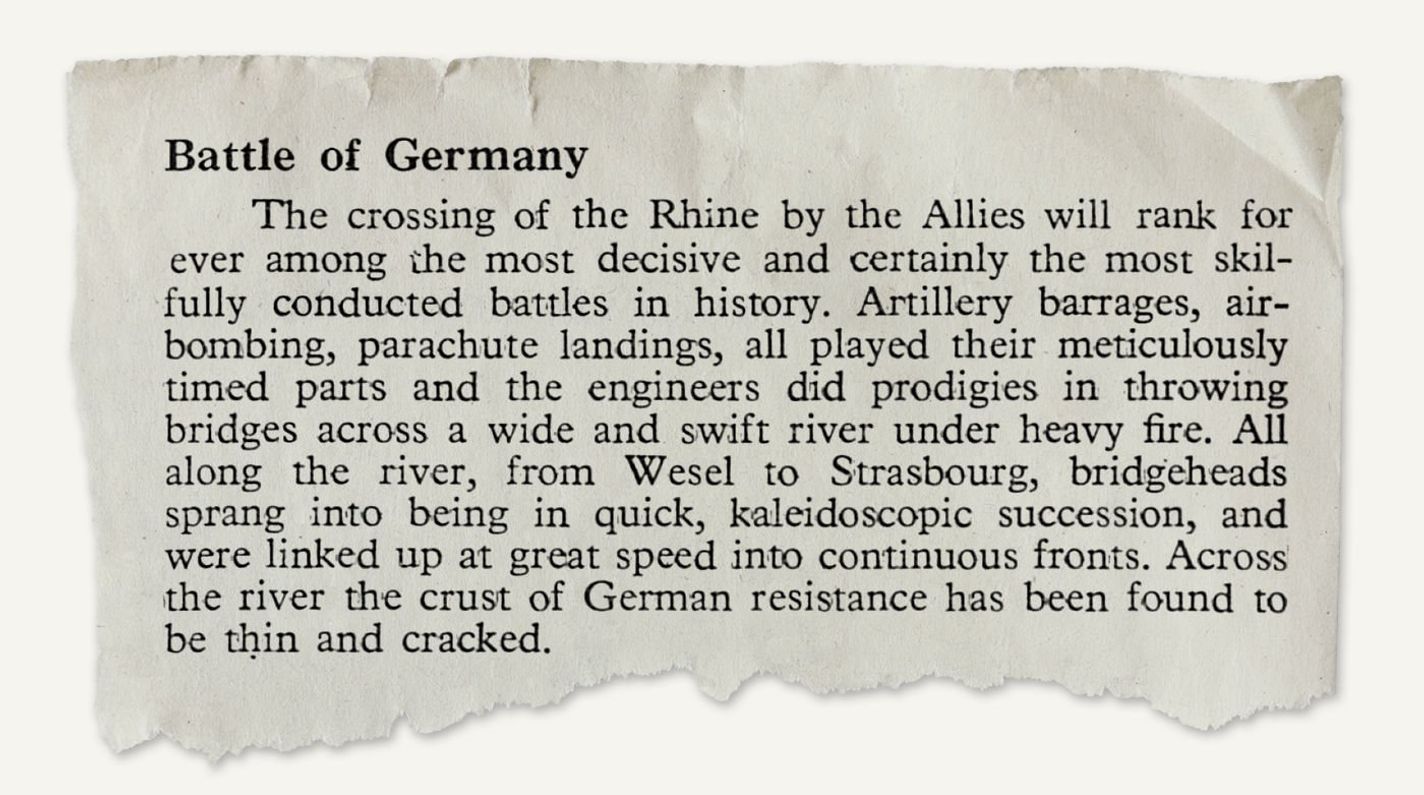

Europe, March 15th 1945

Axis control

Neutral

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

On pre-war borders

sweden

Baltic

Sea

denmark

denmark

North

Sea

Danzig

Stettin

Berlin

POLAND

neth.

britain

neth.

Oder

germany

Cologne

Bel.

czechoslovakia

Rhine

Lux.

AUSTRIA

hungary

switz.

france

yugoslavia

italy

Sources: United States government; Mapping The International System, 1886-2017: The CShapes 2.0 Dataset

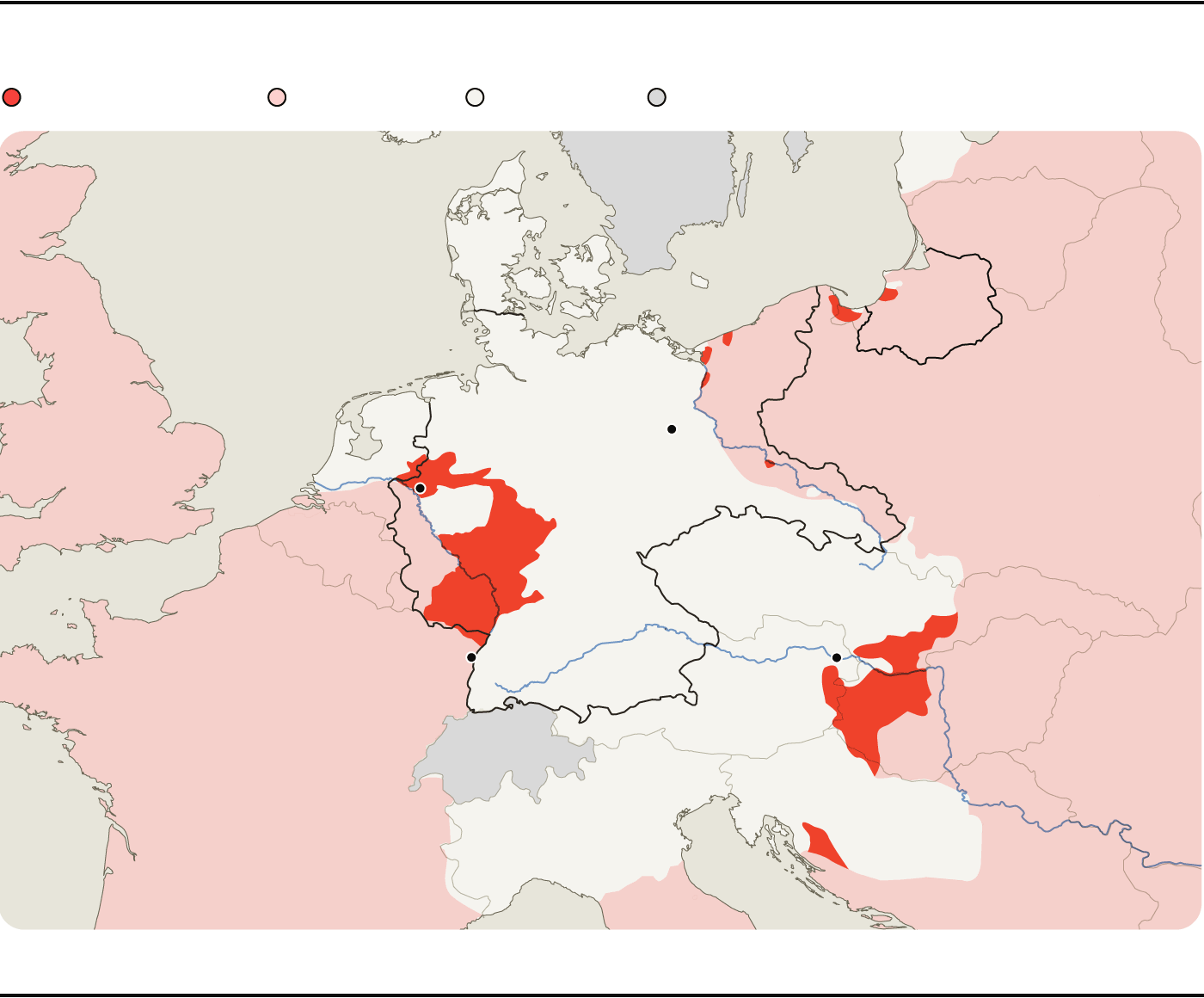

Europe, March 15th 1945

On pre-war borders

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

Axis control

Neutral

sweden

Baltic

Sea

denmark

denmark

North

Sea

Danzig

Stettin

Berlin

POLAND

neth.

neth.

germany

Oder

Cologne

Bel.

czechoslovakia

Rhine

Lux.

AUSTRIA

hungary

switz.

france

yugoslavia

italy

Sources: United States government; Mapping The

International System, 1886-2017: The CShapes 2.0 Dataset

Europe, March 15th 1945

On pre-war borders

Axis control

Neutral

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

sweden

Baltic

Sea

denmark

denmark

North

Sea

Danzig

Stettin

Berlin

POLAND

neth.

neth.

Oder

germany

Cologne

Bel.

czechoslovakia

Rhine

Lux.

AUSTRIA

hungary

switz.

france

yugoslavia

italy

Sources: United States government; Mapping The International System,

1886-2017: The CShapes 2.0 Dataset

“Towards the end of February, Field-Marshal Alexander visited Jugoslavia and conferred with General Tolbukhin, the Soviet Commander-in-Chief in the Balkans, and with Marshal Tito. Presumably, they discussed ways and means to complete the liberation of the Balkans. Nearly the whole South-East of Europe has now been freed, though scattered pockets of German resistance exist throughout Jugoslavia. The Wehrmacht, however, still holds the whole of Croatia as well as the area between Lake Balaton and the Danube in north-western Hungary. These two strongholds cover the approaches to Austria.”

“The political situation in the Balkans and in the Danube Basin is far less satisfactory than the military position. Uneasiness and tension prevail throughout the area. The freed peoples are suffering under two old and familiar scourges: the violence of social and political conflicts and the intensity of an infinite number of nationalistic feuds. Both the internal upheavals and the national conflicts are in one way or another linked with the relations between the great Allied Powers. The old and familiar Balkan problems are reappearing in a form that is only partly new; and they threaten to create international trouble.”

“The disturbing feature of this typically Balkan turmoil is that the local leaders, generals and chieftains apparently hope that they may be able to exploit possible rivalries between the Great Allied Powers in order to further their own claims. Almost automatically a situation has arisen in which the Left, on the whole, looks for assistance to Russia and the Right places its hopes on the intervention of the Western Powers. Vague political calculations are based on the most grotesque assumptions…It is idle to deny that the policies of the Great Powers on the spot sometimes lend colour to such interpretations.”

“Behind the fighting lines of the Russian armies there lie vast expanses of ‘scorched earth.’ That the destruction wrought there has been on a stupendous scale is certain, although that scale varies from province to province and from town to town. A tentative official estimate puts the area of total destruction at 700 square miles. From scores of cities and towns in the Ukraine and White Russia come reports of life shattered to its very foundations. In many towns, out of thousands of houses only a few dozen or a few hundred were left standing after the Germans had been expelled.”

“But the story of destruction, which can be continued indefinitely, tells only half the tale. The other half, which is not less striking, has been told by the reports on the industrial development and expansion that have taken place in eastern Russia during the war, as the combined result of the transfer of plant from the west and of an intensive accumulation of capital on the spot. Recently published figures and statements suggest that the rate of development in the east has been so great that it has enabled Russia’s heavy industries to re-capture their pre-war levels of production, and even rise to above them.”

“By hard labour and unparalleled sacrifices Russia has thus succeeded in winning the war, not only militarily on the battlefields, but also economically, in the factories and mines. In spite of the tremendous devastation in the western lands, it can now find the basis for post-war reconstruction in its newly-built factories in the east.”

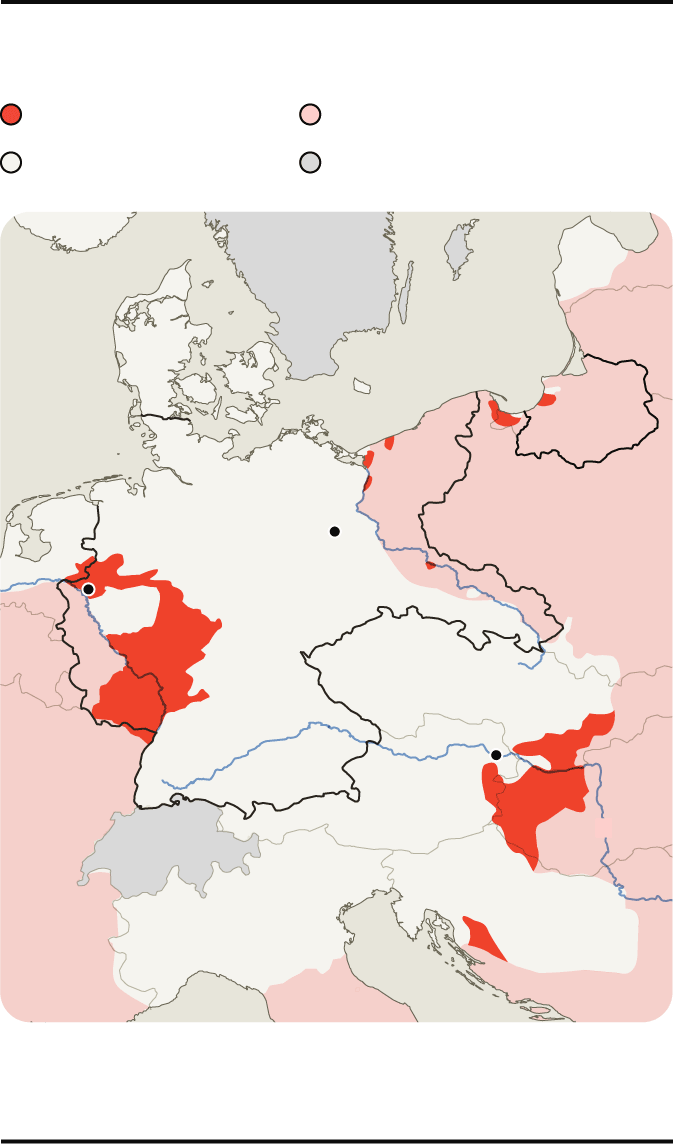

“The crossing of the Rhine by the Allies will rank for ever among the most decisive and certainly the most skilfully conducted battles in history. Artillery barrages, air-bombing, parachute landings, all played their meticulously timed parts and the engineers did prodigies in throwing bridges across a wide and swift river under heavy fire. All along the river, from Wesel to Strasbourg, bridgeheads sprang into being in quick, kaleidoscopic succession, and were linked up at great speed into continuous fronts. Across the river the crust of German resistance has been found to be thin and cracked.”

Europe, April 1st 1945

Axis control

Neutral

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

On pre-war borders

sweden

Baltic

Sea

denmark

denmark

North

Sea

Berlin

POLAND

neth.

britain

neth.

Oder

germany

Wesel

Bel.

czechoslovakia

Rhine

Vienna

Strasbourg

Danube

hungary

AUSTRIA

switz.

france

italy

yugoslavia

Sources: United States government; Mapping The International System, 1886-2017: The CShapes 2.0 Dataset

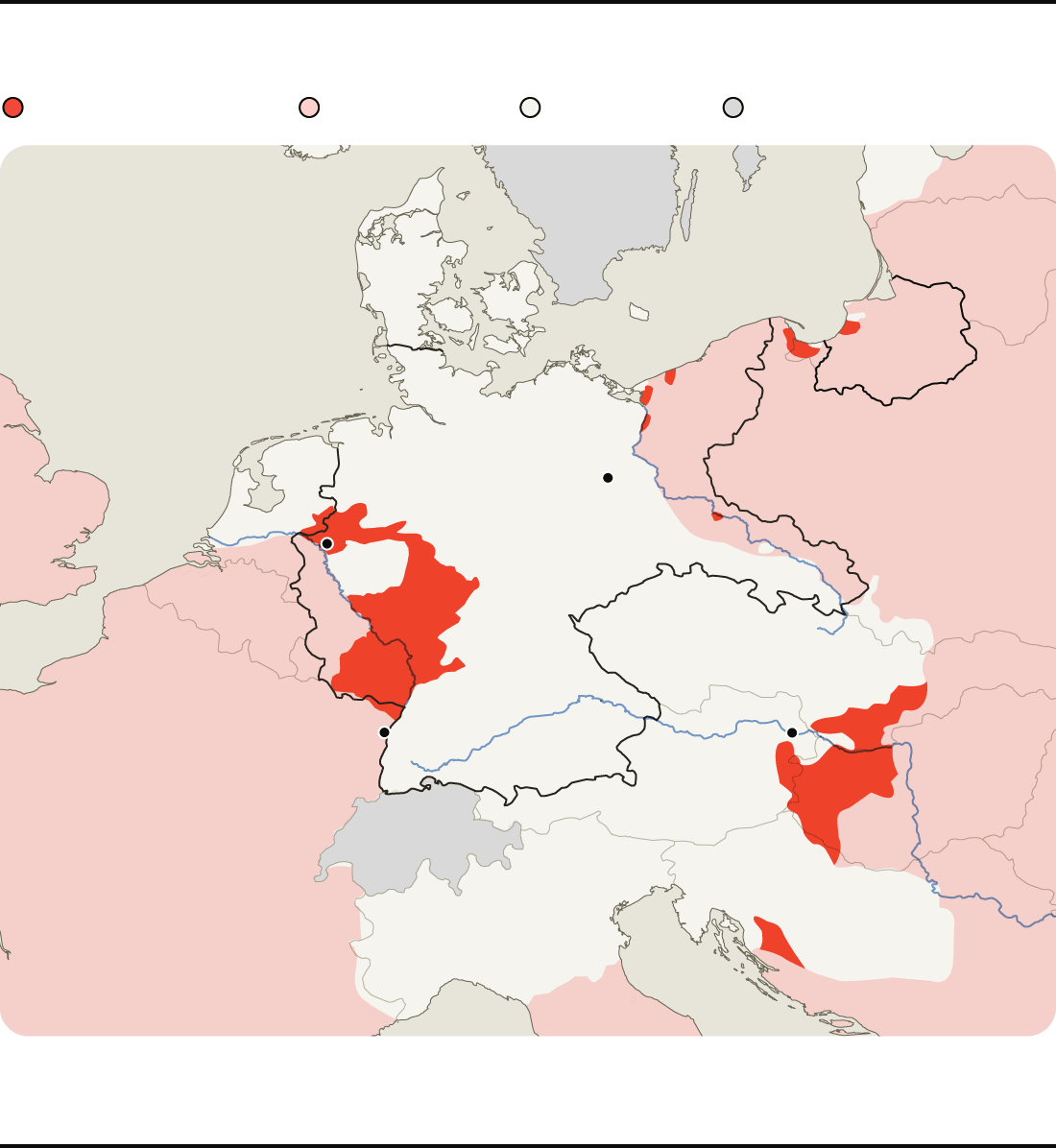

Europe, April 1st 1945

On pre-war borders

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

Axis control

Neutral

sweden

Baltic

Sea

denmark

denmark

Berlin

POLAND

neth.

neth.

Oder

germany

Wesel

Bel.

czechoslovakia

Vienna

Vienna

Rhine

Danube

france

AUSTRIA

hungary

switz.

italy

yugoslavia

Sources: United States government; Mapping The

International System, 1886-2017: The CShapes 2.0 Dataset

Europe, April 1st 1945

On pre-war borders

Axis control

Neutral

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

sweden

Baltic

Sea

denmark

denmark

North

Sea

Berlin

POLAND

neth.

neth.

Oder

germany

Wesel

Bel.

czechoslovakia

Rhine

Vienna

Strasbourg

Danube

hungary

AUSTRIA

switz.

france

italy

yugoslavia

Sources: United States government; Mapping The International System,

1886-2017: The CShapes 2.0 Dataset

“The complete paralysis of transport; the scanty industrial resources of Central Germany, Austria and Western Bohemia, which are all that remain to the Wehrmacht; the appalling condition of the bombed towns; the growing administrative chaos—these things can no longer be passed over in silence by official Nazi spokesmen. Frequent announcements about executions of ‘cowards’ and broadcast appeals to Nazi organisations, and even to civilians, for help in the rounding-up of straggling soldiers and deserters are unfailing pointers to a rapid deterioration in morale. In the last war, it was the home front which, according to the Nazi legend, stabbed the Army in the back. In this war, it looks to the Nazis as if the home front had been stabbed in the back by the Army.”

“The military tasks of the alliance are nearly fulfilled, at least in Europe, but the tasks of peacemaking for the most part still lie ahead. They are certain to put Allied diplomacy to a test much more severe than any of the strains of war. Victory over the common enemy inevitably tends to loosen the ties of solidarity that bind allies in the face of mortal danger. On the eve of victory, and even more on the morrow, differences of outlook and interest reassert themselves.”

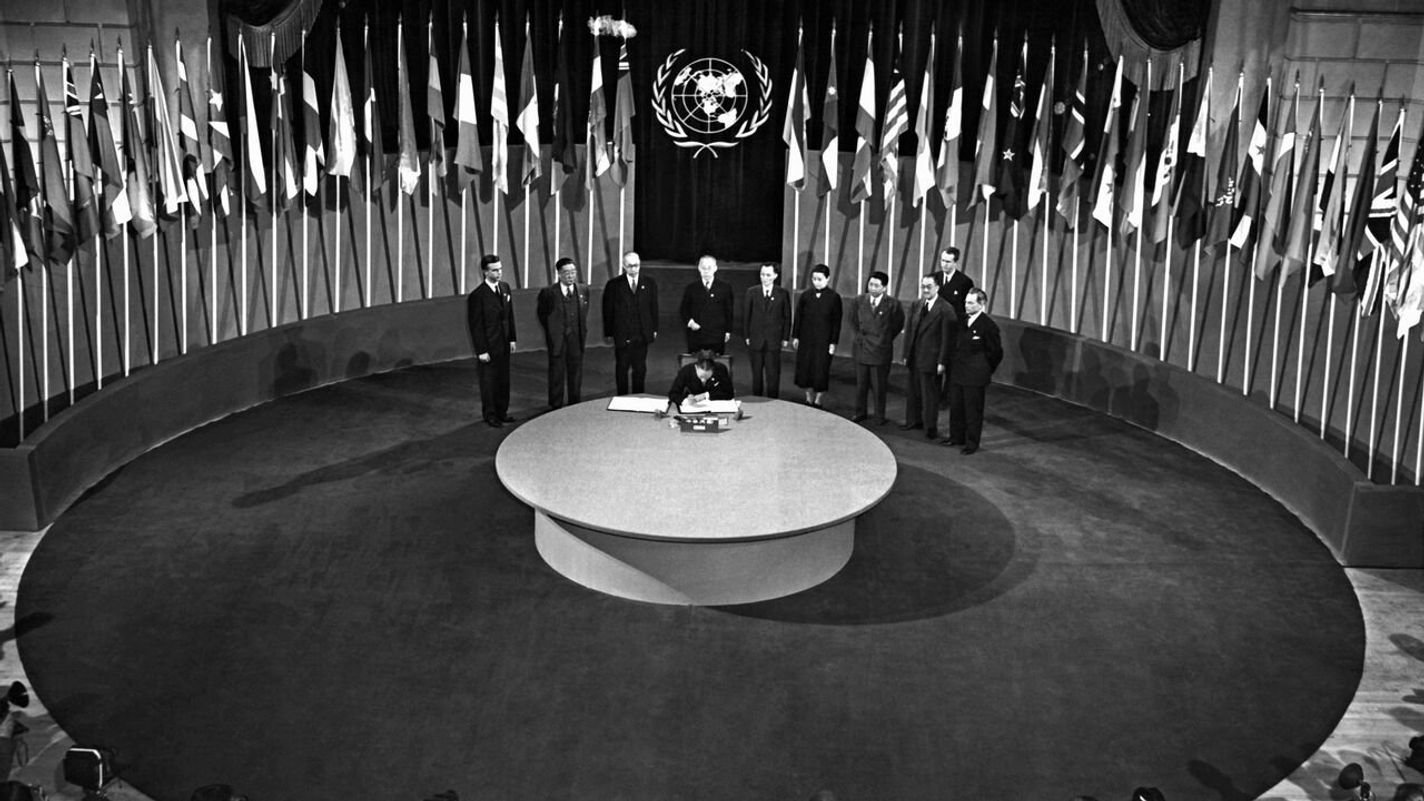

“In the light of these and similar statements, there can be no doubt about the reluctance with which Russia seems to be joining the world organisation. There is, in fact, an anti-League complex colouring the Russian attitude, which has its origin in Russia’s experience with the old League of Nations. Moscow has not forgotten that Russia was the only state against which the most humiliating sanction—expulsion from the League—was applied in Geneva, when so many flagrant aggressions had been treated with mild indulgence. With this Genevan humiliation still freshly in mind, Russia, now victorious and sought-after, is showing an exaggerated anxiety to make her prestige felt at San Francisco.”

“To those who have followed Russian policy, this attitude is a disappointment perhaps, but not a surprise. But unfortunately there has been an official conspiracy, born more of wishful thinking than of the desire to deceive, to pretend that all was going smoothly with the plans for a new, and better, League. This has been particularly so in the United States. The American people, with their tendency to attach magical properties to paper constitutions, would, in any event, have been predisposed to exaggerate the importance of the formal organisation of world order. But they have also recently been subjected to a high-pressure campaign by the State Department to ‘sell’ the Dumbarton Oaks proposals.”

“It would be difficult to find hyperbole strong enough to exaggerate the sense of loss felt all over the free world at the sudden news of President Roosevelt’s death. Never before for a statesman of another country and rarely for one of our own leaders have the outward pomp of ceremonial mourning and also the inward and personal lamentation of the public been more universal and heartfelt. In part, this has been a tribute of gratitude to one who was a very present help in trouble. No Englishman who lived through those twelve dreadful months from June 1940 to June 1941 is ever likely to forget how completely the nation’s hope for ultimate victory rested on that buoyant figure in the White House, and how, stage by stage, the hopes found response in action.”

“It was no accident that found him taking office on the very day the banks closed, or that found him steadily leading the nation to a firm view of its obligations in a world crisis. Friends of the Roosevelt family relate that in the early 1920s, when he had first been ignominiously defeated in his Vice-Presidential candidacy and then been stricken with infantile paralysis, when nothing seemed to be in front of him but the life of an invalid country gentleman, that even then, from his wheel-chair, he prophesied that another great crisis was coming for America and the world, a crisis that could be surmounted only by a strong President pursuing a firm liberal policy, and that he, Franklin Roosevelt the cripple, was to be the man.”

“The eyes of the world are now on President Truman. By one of those extraordinary accidents that can happen only in America, there succeeds to the world’s best-known man one of the world’s least-known men. Although, as has been said, only a single heart-beat separates every Vice-President from the greatest office in the world, his qualifications for holding that office rarely, if ever, enter into the reasons the nominating convention has for its choice. Vice-Presidents are chosen as political makeweights to collect a few votes or (more often) to avoid losing them, and they are almost always obscure figures when they are suddenly thrust into the limelight.”

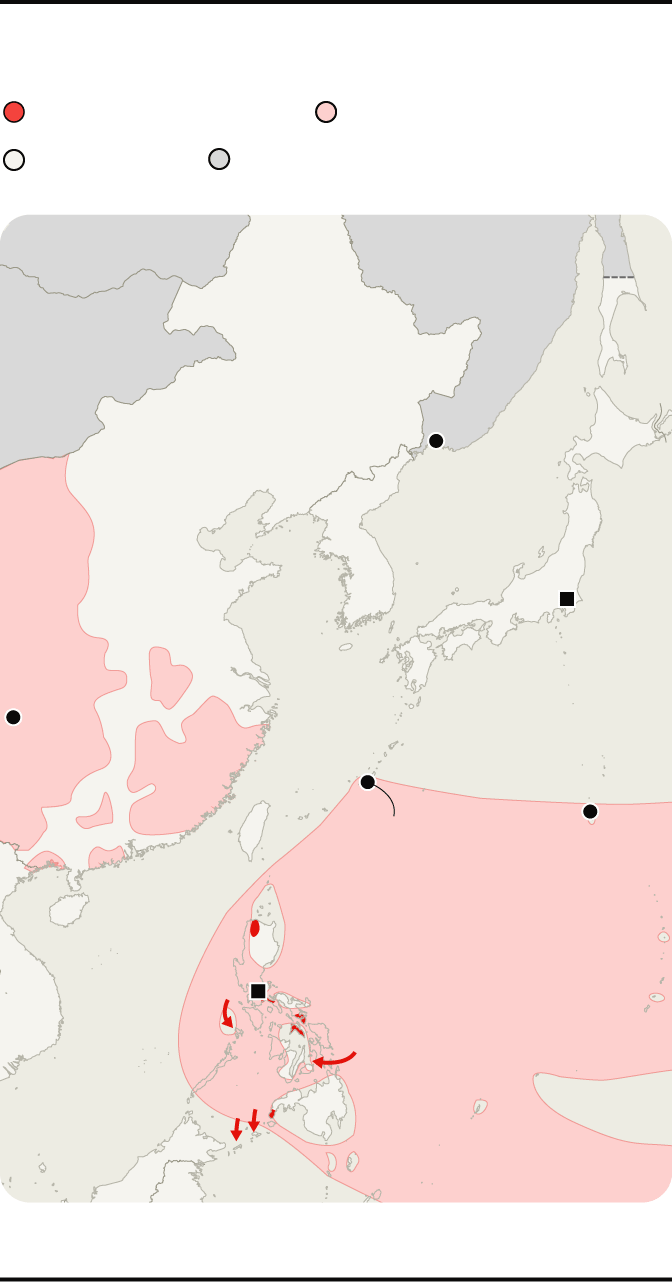

“What are the practical considerations? Generally speaking, war—like peace—tends to be indivisible. The ties of Russia’s alliance with the United States and Great Britain are too manifold and many-sided to allow for her continued neutrality. It is difficult to conceive a situation in which the Big Three should jointly shape a post-war European settlement and discard the partnership at the boundaries of Asia…Russia’s own interests would not permit a division of spheres so eccentric as to deprive her of the benefits which she can expect from the alliance in the Pacific theatre of war.”

South Pacific, April 15th 1945

Neutral

Axis control

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

Russia

Sakhalin

MONGOLIA

Vladivostok

KOREA

JAPAN

PACIFIC

OCEAN

Tokyo

CHINA

Chungking

Okinawa

Iwo Jima

Burma

PHILIPPINES

SIAM

Manila

french

indochina

Source: United States government

South Pacific, April 15th 1945

Neutral

Axis control

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

Russia

Sakhalin

MONGOLIA

Vladivostok

KOREA

JAPAN

Tokyo

CHINA

Chungking

Okinawa

Iwo Jima

Burma

PHILIPPINES

PACIFIC

OCEAN

SIAM

Manila

french

indochina

Source: United States government

South Pacific, April 15th 1945

Recent Allied gains

Allied control

Neutral

Axis control

Russia

Sakhalin

MONGOLIA

Vladivostok

KOREA

JAPAN

CHINA

Tokyo

Chungking

Okinawa

Iwo Jima

PHILIPPINES

PACIFIC

OCEAN

Manila

Source: United States government

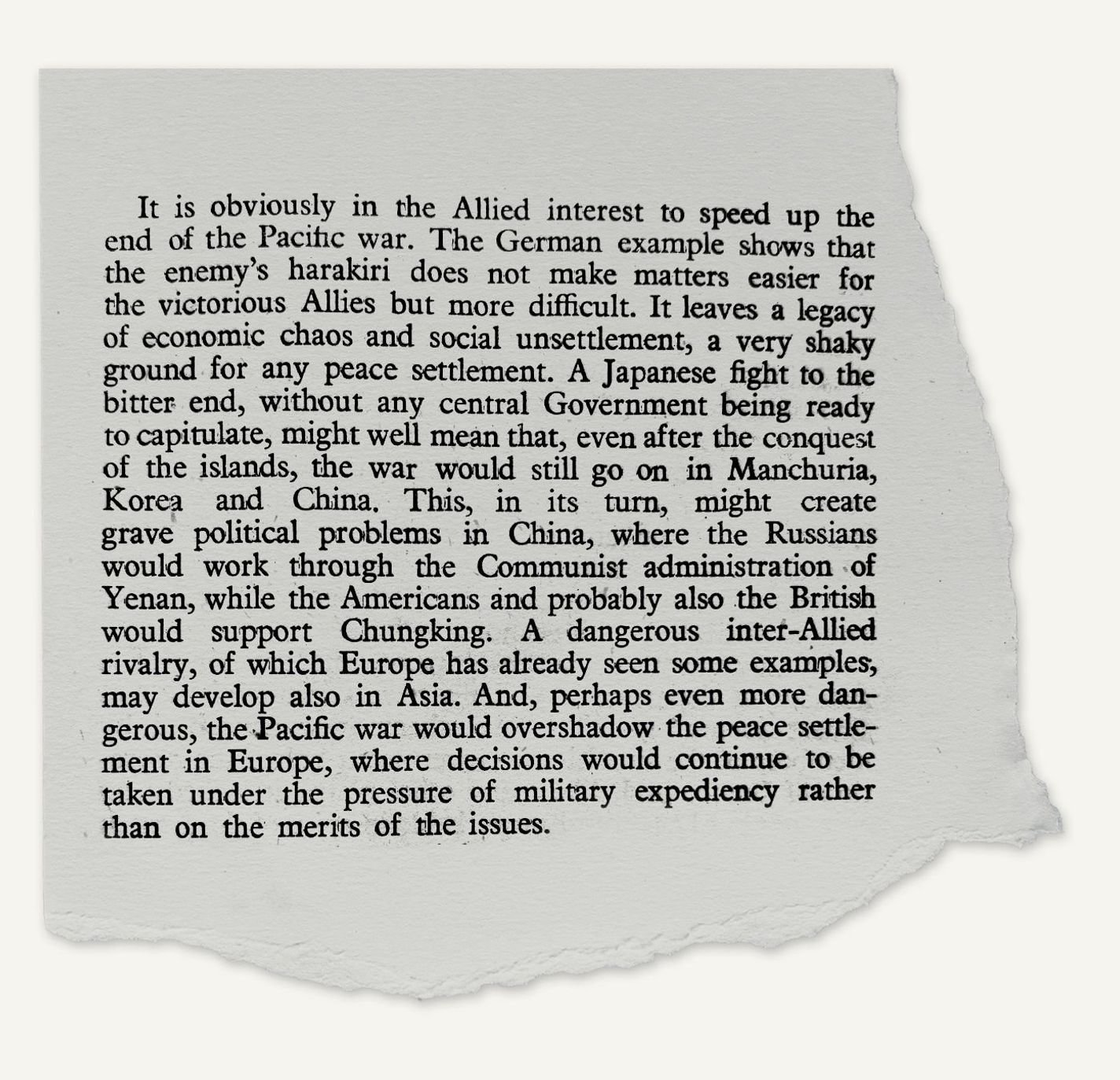

“It is obviously in the Allied interest to speed up the end of the Pacific war. The German example shows that the enemy’s harakiri does not make matters easier for the victorious Allies but more difficult. It leaves a legacy of economic chaos and social unsettlement, a very shaky ground for any peace settlement. A Japanese fight to the bitter end, without any central Government being ready to capitulate, might well mean that, even after the conquest of the islands, the war would still go on in Manchuria, Korea and China. This, in its turn, might create grave political problems in China, where the Russians would work through the Communist administration of Yenan, while the Americans and probably also the British would support Chungking. A dangerous inter-Allied rivalry, of which Europe has already seen some examples, may develop also in Asia.”

“Mussolini is dead. So, according to general belief, is Hitler, though the world has not yet been given the spectacle of his corpse being kicked around the streets as proof of death. Whether he has really cheated justice, or is merely trying to escape it; whether he has met a soldier’s death or the gibbering dissolution of a lunatic; whether he died of natural causes, or by his own hand or shot by some other member of the gang—all these are questions that for a few more days will have to go without answers.”

“The slow asymptotic approach of the end during these last few months, always nearer but never quite reached, will make the hour of acknowledged victory, when it arrives, something of an anti-climax. This will be no grand climacteric like November 11, 1918, but one more stage reached and overcome in a world crisis that has been raging for thirty years and has many storms ahead. The moment of rejoicing will be brief, and the rejoicing itself will be restrained by the knowledge of efforts and sacrifices still to come. But a moment there will be, and though verdicts must be left to history, this, the hour of surrenders and capitulations, of liberty and victory, is the time for tributes.”

“The war has been fought with skill as well as with courage. Just as in its personal aspects, the sordid end of the gangsters, caught like rats in a trap, is one of History’s monumental vindications of the moralities, so in its political aspects, the end of the war is an irrefutable proof of the values of liberty. Once again, demonstration has been given of the immense moral and physical resources upon which a free and tolerant and honest society can call. The British people have fought this war longer than most, more continuously than any, harder than many. They have fought it, in the field and at home, at sea and in the air, with technical skill and physical courage and great human qualities of imagination. Hitler called them military imbeciles; and that is why once again they have made magnificent soldiers.”

“On Tuesday the firing ceased, and Europe, though a long way yet from peace, was no longer at war. Germany is totally occupied. Apart from the Doenitz-Krosigk phantom, there is no German Government. The German people, in General Jodl’s anguished words, are for better or worse delivered into the victors’ hands. In the middle of Europe, where so recently there stood the most powerful and resourceful military tyranny the world has ever seen, there is now nothing but the emptiness of sorrow and silence.”

“These are days of many emotions. Uppermost, quite naturally, is that of thankfulness that the long ordeal, for half the world at least, is over, and that the sins of blindness and indolence and complacency that encouraged the aggressor—sins from whose taint none is free—are purged at last. It is right that there should be a brief pause of rejoicing.”

“The period of physical courage and physical sacrifice is nearing its end. The need will now be for moral courage and mental sacrifice, if the opportunity so dearly purchased is to be taken. The quieter virtues are no less difficult, especially for a generous, tolerant, easygoing people who are slow either to anger or to forethought and quick both to forgive and forget. But if the tasks of peace can be approached with the same majestic compound of unity in freedom and responsibility that has brought the British people so triumphantly through the perils of these dreadful years, then nothing will be beyond their powers.”

“…the root and basis of Japanese aggression lies in the Japanese homeland. The reconquest of Malaya and the Netherlands Indies is an end in itself. It does not directly contribute to the immediate defeat of Japan. The battles in the inner ring of the Japanese defences have not so far proved as decisive as the distant fighting. The effects of heavy air bombardment are always difficult to assess and no one can say precisely what is their contribution to the destruction of the enemy’s war industries and civilian morale. Yet the air raids on the Japanese mainland already constitute a major offensive.”

“In many ways, the political outlook could hardly be more gloomy. Japan has been deserted by its one ally, and the Japanese press’s indignation at this defection reflects their uneasiness. Germany’s downfall is an impressive warning to any nation bent on fighting until ten minutes past twelve. Moreover, the end of the European war frees the Russians for political and military action in the Far East. Their first move was the denunciation of the Soviet-Japanese Pact of Neutrality. Is the next step open or undeclared war? If so, might not Japan, surrounded by enemies, prefer to offer unconditional surrender, hoping by shortening the war to secure better terms?”

“All this is familiar. It is even difficult to grasp the magnitude of the problem, so accustomed are we to ruin and devastation. Yet what a challenge it presents. To restore a functioning system in these lands ravaged by battle and distorted by years of Hitler’s war economy is a more formidable task than the actual waging of the war. Not only is the problem itself more complex, but the machinery is lacking to accomplish it properly.”

“The difficulty in adapting this military administration to the needs of Europe lies in the fact that hitherto its job from the first planning to the last execution has been a straightforward one, based on a very simple objective—to win the war. As a result, the priorities have been simple—military needs first. And this in turn has simplified administration. Now the objective is very complex—to restore a shattered continent. The priorities are correspondingly complex. And behind all the complexities, a primary decision has to be taken which military authorities will naturally find it very difficult to take. Civilian, not military, needs must now come first.”

“Their object is to re-set a standard of international behaviour. The cases are to be heard on a basis of evidence. Only the guilty will be punished. There will be no indiscriminate reprisals. Punishment will be inflicted for crimes, not political offences. The theory underlying the whole unpleasant task is that impunity for offenders against every canon of human decency would have a pernicious effect upon international morality.”

“The more complicated class is that which has committed crimes against Germans or against more than one nationality or against mankind in general. Here some new form of international court is required; there is no precedent for trying war crimes through channels of organised international justice. If the recommendations of the War Crimes Commission are followed, the indicting nations will not find it too difficult to agree on the procedure for trying a small class of the ‘major criminals’ of whom Goering is the prototype. Their chief difficulty will be in deciding where to draw the line among the lesser fry, particularly among the tens of thousands of captured SS.”

“It is not to be taken for granted that trials will serve this purpose any better than dogs’ deaths such as that which befell Mussolini. If they are to do so, they must be summary and they must be unspectacular. To allow prisoners the luxury of famous last words in a Hollywood setting would be to defeat the United Nations’ purpose. So would delays during which Europe might sicken with the smell of foul deeds gone stale.”

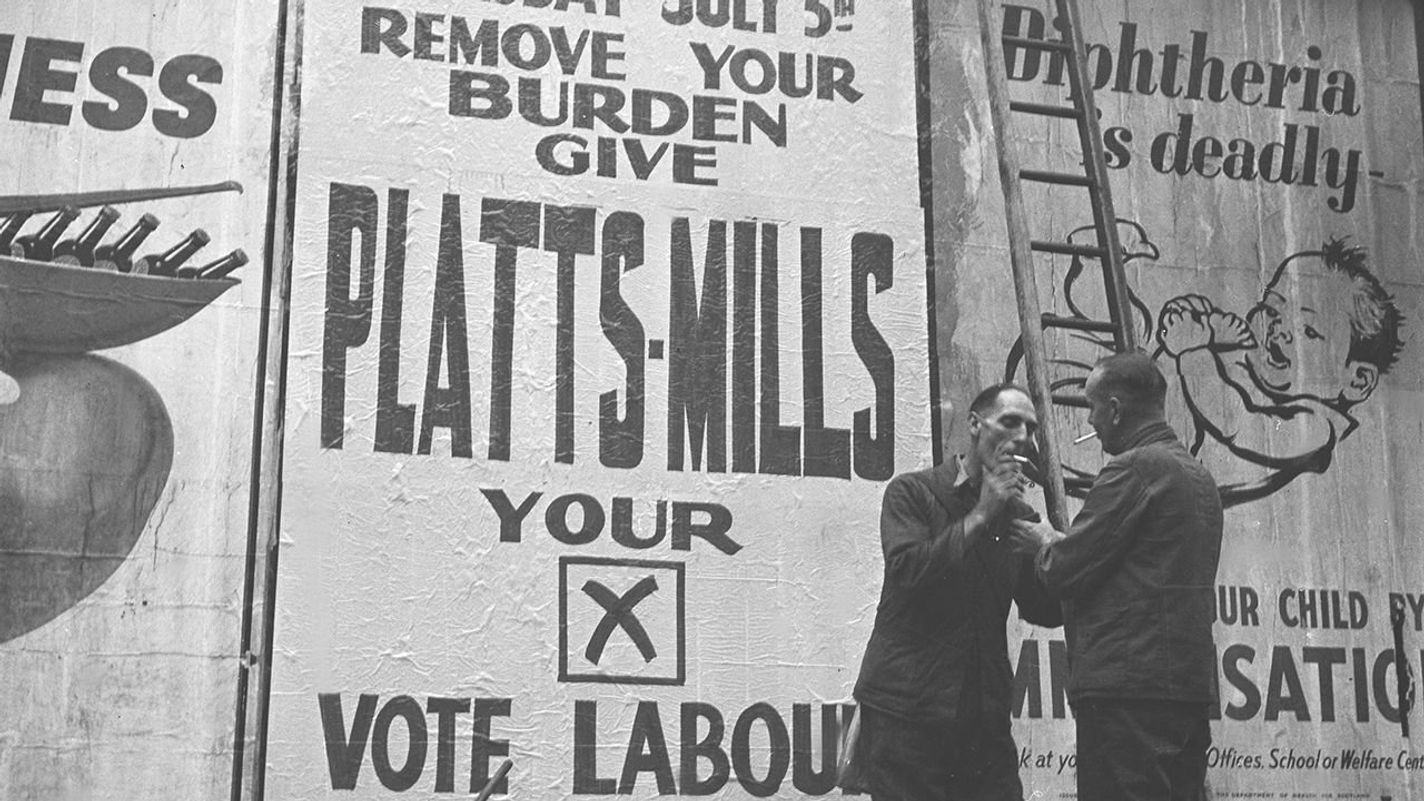

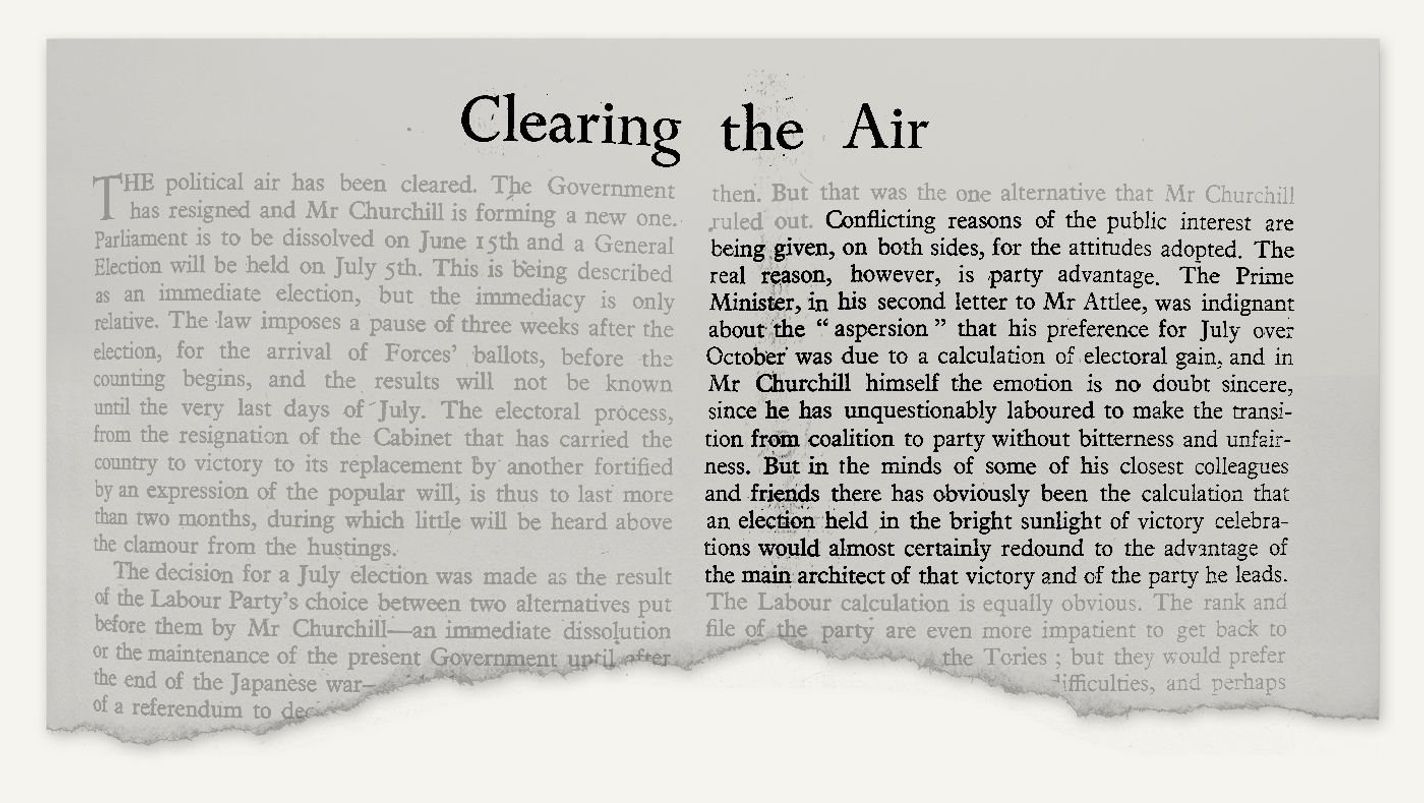

“Conflicting reasons of the public interest are being given, on both sides, for the attitudes adopted. The real reason, however, is party advantage. The Prime Minister, in his second letter to Mr Attlee, was indignant about the ‘aspersion’ that his preference for July over October was due to a calculation of electoral gain, and in Mr Churchill himself the emotion is no doubt sincere. But in the minds of some of his closest colleagues and friends there has obviously been the calculation that an election held in the bright sunlight of victory celebrations would almost certainly redound to the advantage of the main architect of that victory and the party he leads.”

“It is very difficult to foresee the result of the contest thus joined. The general expectation, even among many Labour people, is that the Conservative Party will return with a majority, though a reduced one, and that this result will be a personal vote of confidence in Mr Churchill. This, no doubt, is the most probable result. But it is by no means certain.”

“A general election, especially after so long an interval and such tremendous events, ought to be regarded as an opportunity for a great regeneration of national purpose. That it is not so regarded by the man in the street, but rather in the guise of a resumption of normal sporting events, comparable to a cricket Test match (and almost as lengthy), reflects the fact that there is a total lack of enthusiasm for either of the major parties.”

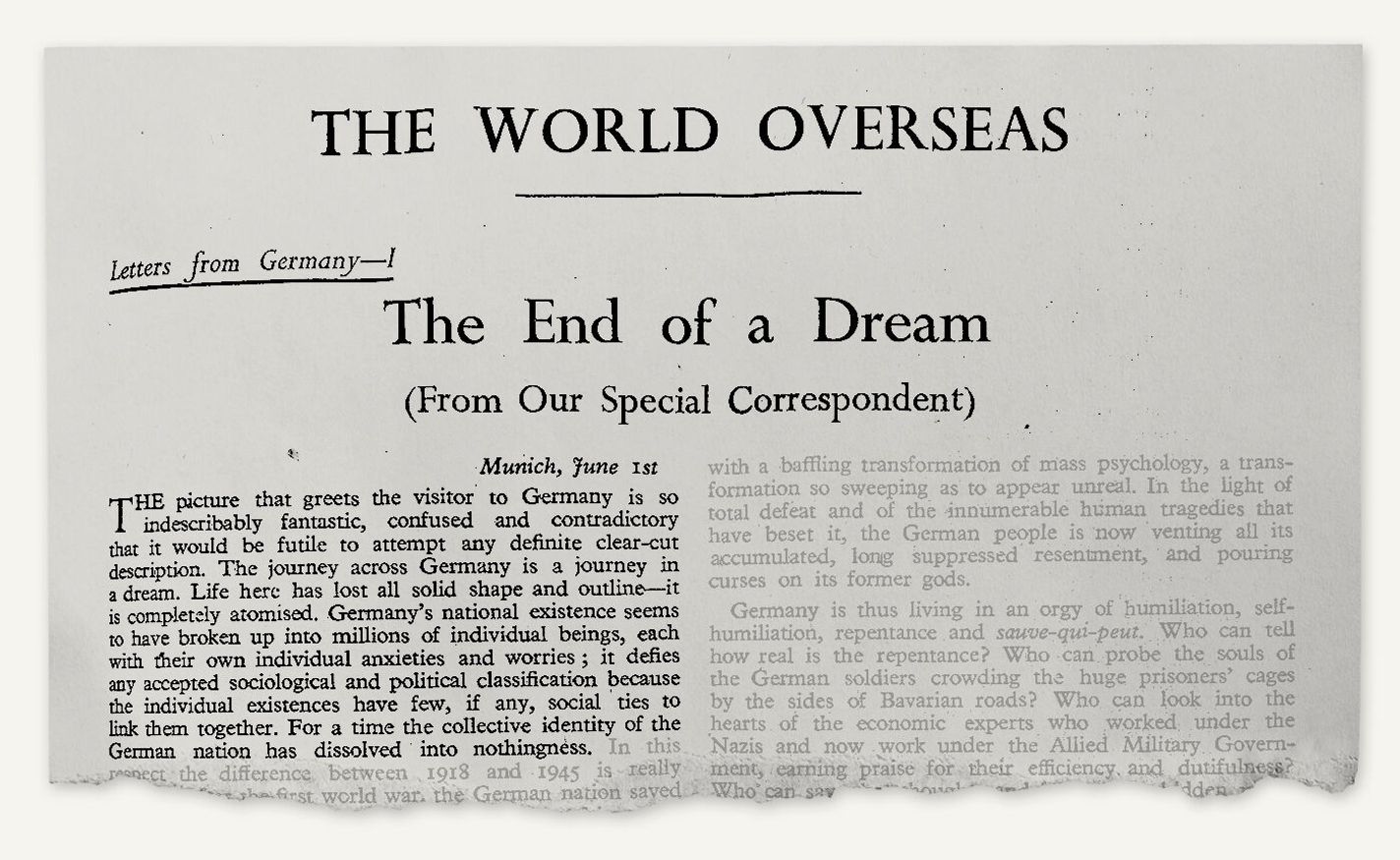

“The picture that greets the visitor to Germany is so indescribably fantastic, confused and contradictory that it would be futile to attempt any definite clear-cut description. The journey across Germany is a journey in a dream. Life here has lost all solid shape and outline—it is completely atomised. Germany’s national existence seems to have broken up into millions of individual beings, each with their own individual anxieties and worries; it defies any accepted sociological and political classification because the individual existences have few, if any, social ties to link them together. For a time the collective identity of the German nation has dissolved into nothingness.”

“Here, in Bavaria, the Kadaver-disciplin quite obviously broke down in the last days or weeks of the war—it had shown some faint cracks even before. Munich was officially called the ‘Capital of the Movement.’ In the centre of the city there stands the Mecca of National Socialism, the famous Beer Hall, now guarded by an American sentry, presumably as a grotesque relic of some museum value. Yet in this ‘Capital of the Movement,’ it is almost impossible to find anybody to attack the Nazi record. The citizens timidly tell the foreigner that Munich’s half-jocular and unofficial title was ‘the Capital of the Counter-Movement.’ Even in the hey-day of Nazism the local intelligentsia took delight in discreetly pin-pricking the Nazis on the stage or in timidly displaying an archaic sentiment for the old Wittelsbach dynasty. For the Bavarian Left, which occasionally attempted some less innocent gestures of opposition, there was the nearby Dachau concentration camp, which never failed to act as a tremendous damper on any anti-Nazi reflexes in the Bavarian mind.”

“The first shoots of a new political life in post-Nazi Bavaria are, of course, pathetically weak and anæmic. All political matters are concentrated in the officers of the Military Government and in the private homes of a few survivors of the Weimar democracy. The leaders of the new Bavarian administration act as individuals without the backing of any organised bodies of political opinion. The formation of such bodies has been strictly prohibited by the Military Government, which has made it more than sufficiently clear that there must be ‘no politics in Germany,’ and that the ban on political activities applies to all anti-Nazi groups without distinction.”

“The population of the Russian zone has, however, been very considerably reduced by the flight of German civilians and by the mass surrenders of the German armies to the Western Allies. The disproportion which existed in pre-war Germany has thus been accentuated. Unless the transfer of labourers eastwards and the despatch of foodstuffs westwards can be speedily arranged, the food in the East will not be harvested for lack of hands and the West will starve for lack of supplies. The problem can be solved only if the Allies deal with it jointly.”

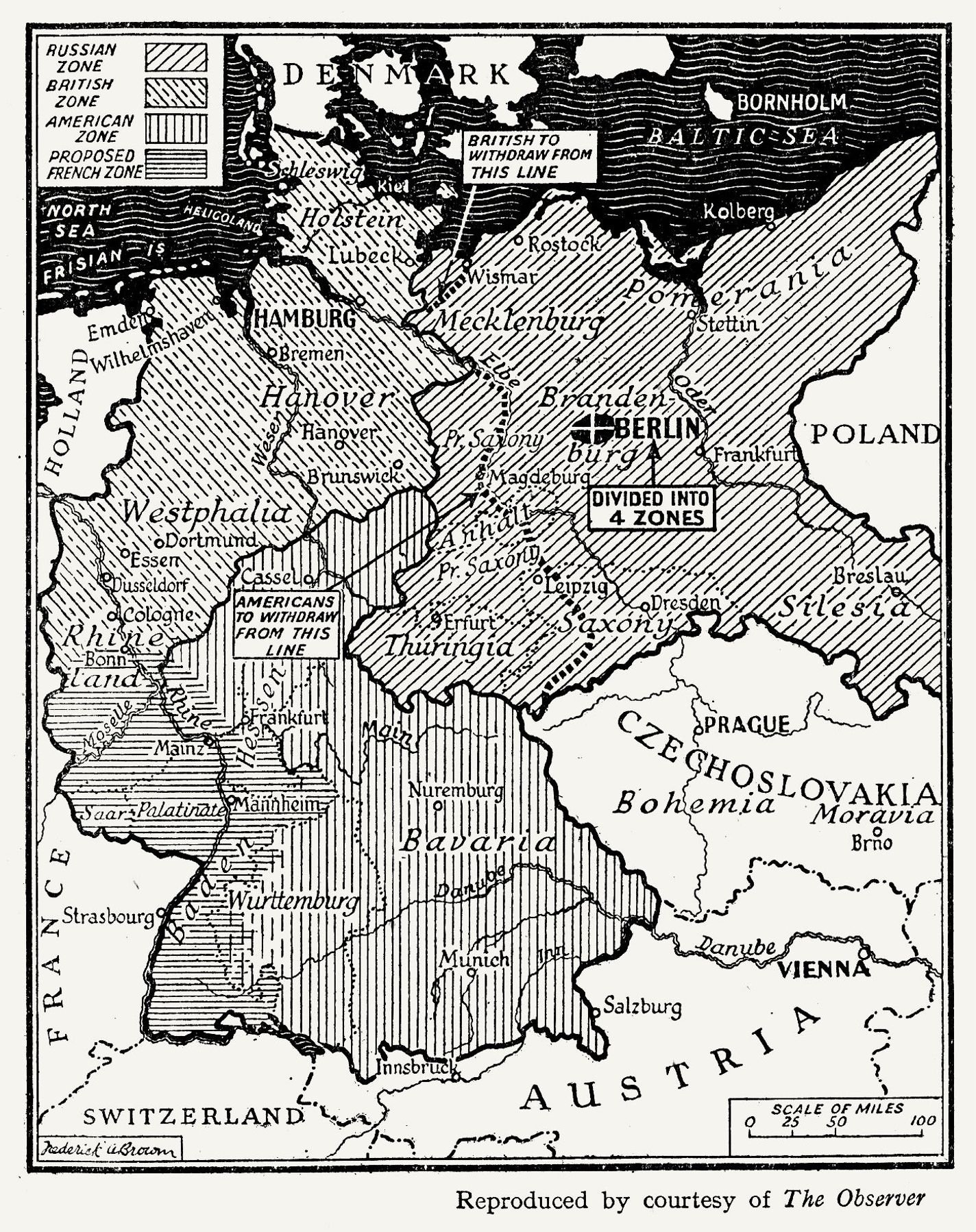

“Is the Allies’ policy for Germany to destroy for ever the single centralised state? If so, is this to be done merely by decentralisation or by federation? Or are independent states to be carved out of the old Reich? Or is it intended to split Germany by drawing the different zones permanently into the ‘sphere of influence’ of one or other of the victors?”

“One last point of divergence is the picture the various victors give the German people of their future. The British and the Americans are silent. They make no propaganda. They put across no line. Their radio stations still give little but lists of prohibitions and penalties. Berlin radio, on the other hand, gives the Germans a glimmer of hope that if they work hard and eliminate their own Nazis they will one day, with ‘the help of the great Soviet Union’ find their way back to the world of nations. Mere broadcasts may be dismissed as a propaganda stunt. If so, it is an effective one. The darkness before the Germans is so impenetrable and their fate is so irrevocably out of their hands that any sign of a policy, any hope of a positive future cannot fail to stir their minds and make them look, however uncertainly, to a dawn of hope in the Eastern sky.”

“The Charter cannot be accused of excessive idealism. On the contrary, almost every article is marked with the experience of two grim decades between the wars during which, in Europe especially, power politics, imperialism and aggression grew up like tenacious ivy within and over the brave new League. In the United Nations Charter, there is no reliance upon better and more idealistic methods of conducting international relations. The dominant position is occupied by those whose physical power would give them a dominant position in any unorganised world society.”

“Did not the belief that the League transcended the Powers which were its members, that the Covenant was in itself a guarantee against war and that collective security was an alternative to national defence and not an extension of it—did not these illusions make the chance of keeping peace more, not less, difficult? Collective security, by making the checking of aggression the responsibility of all, left it the responsibility of none.”

“The conference itself has already shown how powerful the effect of world opinion can be on the policy of great States and how salutary the public airing of injustice and heavy handedness can be. As a forum of world opinion, the international structure of the new League can play a direct part in checking wrongdoing and aggression.”

“South of Munich, against the sharp background of the Alps, can be watched the last scenes of the Wehrmacht’s surrender. Long convoys of lorries crammed with German soldiers, preceded by officers in staff cars, roll on to assembly points and prisoners’ cages. The soldiers are disarmed, some officers—Luftwaffe, SS, infantrymen—still carry their side-arms, and shout loudly in the typical feldwebel fashion their last orders to the men.”

“Somewhere by the side of the road a man in the striped uniform of the concentration camp is trudging slowly home. A short time ago he was stopped by an SS officer, travelling with his orderly in a car. A sharp exchange of words and threats accompanied by violent gesticulation takes place. As an American jeep approaches the quarrel stops, and the SS officer’s car moves off. The ex-inmate of the concentration camp explains with some pride that he was an official of the Social Democratic party at Breslau. Yes, it is true. SS men occasionally bully people like this on the roads.”

“At the other side of the road, a tall, thin woman tries to explain something in broken English to two American officers. In her confused, unintelligible story two words keep on recurring: Gas-kammer. It turns out that seven years ago her child was classified by a Nazi doctor as mentally defective. The family doctor disagreed with the diagnosis, but his opinion was ignored. In accordance with the rules of ‘racial hygiene’ the child would have to be thrown into a gas-chamber, the Nazi version of the Tarpeian rock. The mother hid the child in a remote place, some two hundred kilometres away. The last time she saw the child it was nearly starving. Could she now get a permit from the Military Government to go and fetch her child?”

“But on the national stage, in the newspapers and on the wireless, the roles have been reversed. Here the Labour Party has conducted its campaign with great dignity and good feeling, while the Conservatives have resorted to stunts, red herrings and unfair practices to an extent that has disgusted many of their friends and followers—and, if the truth could be told, most of their leaders outside the charmed circle. The constructive moderation of Mr Eden, Mr Butler and Sir John Anderson has, with the Prime Minister’s active help, been overridden by the circus.”

“When all is said and done, they have not encouraged very many hopes that either of the major parties would confront the enormous and novel tasks of the next few years with the energy that the predicament of the country requires. Such things as foreign and imperial policy, the maintenance of the enormous burden of external indebtedness, the preservation of industrial peace and social unity—all these things require heavy efforts, great skill, a willingness to try new methods, clarity of thought and high courage.”

“Some day there will be a re-alignment of political forces behind which the capacities of the nation can be mobilised for peace as they were in 1940 for war. Mr Churchill could have started the second task as he has finished the first. He made it difficult for himself by accepting a party leadership, and his behaviour in this election has made it finally impossible for him to serve as the rallying point for a truly national policy of social and economic regeneration.”